Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Yorgos Lanthimos

Stars: Colin Farrell, Rachel Weisz, Lea Seydoux, John C Reilly, Ben Whishaw, Roger Ashton-Griffiths, Jessica Barden, Angeliki Papoulia, Michael Smiley.

The films of Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos (Dogtooth, etc) are strange, off beat, enigmatic, unsettling, confronting, and often hard to fathom, and have divided audiences. The Lobster, his first English language feature film, is no exception, and will probably go down as one of the weirdest films to hit screens this year. It won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival this year, but like a lot of previous such winners it is a film that lacks broad commercial appeal, but will find its niche on the festival circuit.

Like Dogtooth, The Lobster is a surreal and uncomfortable comedy/drama set in a strange, closed and oppressive community with its own rules and structures where deviation is severely punished. Lanthimos and his regular collaborator Efthimis Filippou quickly establish the rules of this society in broad strokes, and they explore themes of tyranny, love, freedom versus control and individuality versus the group dynamic in society. Can this also be seen as some sort of satire on the parlous state of modern Greece? Or is that reading too much into the film?

This bleak, absurdist comedy is set in a dystopian society in the not too distant future where single people are arrested and transported to a creepy luxurious hotel run by the formidable Olivia Colman. There they are given 45 days in which to find their soul mate, otherwise they are transformed into an animal of their choice. Each new arrival has one hand cuffed behind their back to reinforce the notion that one can’t really do much alone. They mix awkwardly at dinners and dances, and watch the staff perform small vignettes on the advantages of being a couple.

One such guest is David (played by a slightly pudgy Colin Farrell) , a divorced architect whose strange journey we follow. When questioned about what animal he would like to become should he fail to find a mate, David answers with “a lobster”, thus giving the film its title. Apart from David, we never learn the names of the other characters who are simply listed in the credits according to their disability, such as “the lisping man”, etc.

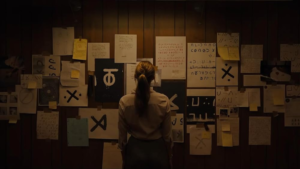

The guests also have the opportunity to extend their stay by hunting down “loners”, rebellious runaways who have fled the hotel for the nearby forest and freedom. But the people who live in the forest also have their own set of rules, and relationships are discouraged and any romantic attachment is severely punished. When David escapes into the forest he meets the tribe led by militant outcast Lea Seydoux, who imposes her own set of rules on this society which is just as harsh as the one he has fled, and which forbids intimacy. He forms a strong bond with the “short sighted woman” (played by Rachel Weisz) and they work to ensure their own survival.

A third world is the nearby city – pristine, cold, sterile and seemingly impersonal – and we briefly visit it, but it exists only to offer another contrast to the other two worlds. Visually, Lanthimos draws a strong contrast between the bleak and dreary beige decor of the hotel, the wide open spaces of the forest which seem gloomy, and the modern city. His vision is enhanced by the cinematography of his Dogtooth lenser Thimios Bakatakis, who shot the film on the windswept coast of Ireland.

This is a jarring and unusual film that offers up a scathing allegory on contemporary society and its strictures and rules, and it also explores concepts of individuality and modern relationships, that need for a connection. Those familiar with the director’s previous films will have some idea what to expect here. The bleak tone is leavened by touches of deadpan humour, and Lanthimos’s direction is extremely mannered and measured. The dialogue is delivered in deadpan style, almost monotone and without inflection.

Lanthimos has attracted a strong international cast that includes Weisz, Colman, John C Reilly, Ben Whishaw, and Lea Seydoux as some of the oddball characters. Cast largely against type, Farrell brings a frailty and fragility to his role as David, a broken man both emotionally and spiritually, and he comes across as awkward and ungainly, certainly not the confident and sexy man of action he often plays on screen. It was a role originally intended for Australian actor Jason Clarke (Everest, etc), who would have been a more comfortable fit with the character.

Weisz’s voice over narration is droll and literate, but comes across almost as if she is reading the words from the page of a novel. And she sometimes describes the action that we are seeing on the screen, a device that becomes a little distracting.

The Lobster is quirky and intriguing and ambiguous for much of the time, but once it leaves the confines of the eerie hotel for the wider outside world it loses its way and much of its impact, and outstays its welcome. Something of an acquired taste for those looking for something slightly left of centre The Lobster will have limited appeal to mainstream audiences.

★★★