Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Simon Stone

Stars: Geoffrey Rush, Ewen Leslie, Miranda Otto, Paul Schneider, Sam Neill, Odessa Young, Anna Torv, Nicholas Hope.

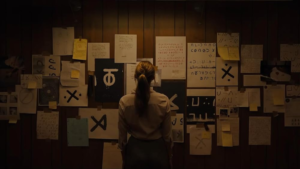

Noted theatre director Simon Stone makes his feature film directorial debut with this dark and moody drama about dysfunctional family relationships, and how secrets from the past can have a devastating impact on the present. The Daughter is a reworking of Ibsen’s 1884 play The Wild Duck, which Stone directed to much acclaim for the Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre a couple of years ago.

The film is a morality play set in a small timber town that is slowly dying. It is an exploration of the human condition and examines rich themes of family, community, secrets and lies, guilt, honesty, the impact of the past on the present, and ideals of Australian masculinity. This moody drama is also reminsicent of other powerful Australian dramas like Lantana and Jindabyne as it looks at a number of relationships and the tiny ripples that disrupt the orderly life of a community.

The timber mill used to be the life blood of the town, providing jobs and a sense of community. But now businessman Henry (Geoffrey Rush) is closing the mill down, pleading changed economic circumstances. Many people are out of work and at a loss how to survive. Families are leaving town for greener pastures, which has a flow on effect on other local businesses. There is plenty of resentment too, especially since Henry is spending a small fortune on his upcoming wedding to the much younger Anna (Anna Torv, from tv series Fringe, etc), his former housekeeper.

Henry’s son Christian (Paul Schneider, from Water For Elephants, etc), who has been working and living in New York for many years, returns home for the nuptials. He reconnects with his former school friend Oliver (Ewen Leslie, from Dead Europe, etc), who has remained in the town and worked at the mill. Christian also meets Oliver’s family, including his wife Charlotte (Miranda Otto) and vulnerable and emotionally fragile daughter Hedvig (Odessa Young, recently seen in Looking For Grace). Oliver’s family has a shared history with Christian’s.

Christian is full of self-loathing and unable to deal with his own personal demons or come to terms with his own troubled relationship with his father. He blames Henry for the suicide of his mother. His own wife is about to leave him, and he is resentful of Oliver’s seemingly happy life and family. Then Oliver discovers a secret about Charlotte that, when revealed, tears the family apart with devastating consequences.

For his first feature film Stone has assembled an A-list ensemble cast that includes Rush, Sam Neill, Otto and Leslie, who deliver strong performances and flesh out the deeply troubled and flawed characters. All of the characters here are emotionally wounded and damaged, a bit like the symbolic duck of the title.

Rush portrays the family patriarch as arrogant and aloof, a thoroughly unlikeable and unpleasant character. Young brings an emotional fragility to her Hedvig, and this is a much more persuasive performance than the recent Looking For Grace. Leslie, who also appeared in Stone’s stage production, captures that damaged psyche of a man betrayed, the prodigal son who returns home after years away and uncovers dark secrets and opens old wounds. Neill brings gravitas to his small role as Walter, Oliver’s father, and a man slowly losing his grip on his faculties and his family, and he earns our sympathy.

Stone develops a pervasive atmosphere of distrust and slow burning anger as the narrative progresses, and the film has the look and feel of some of the early Dogme films, in particular the searing Festen. Despite his theatrical background Stone displays a fine eye for the cinematic with his staging of the material. The Daughter looks good though thanks to Andrew Commis’ evocative cinematography that captures images of the misty rural setting and the surrounding woods and this depressing, dying town. However, at times it reminded me of the film Fell, a rather grim story of revenge set in logging country. Mark Bradshaw’s haunting cello and piano driven score is evocative and adds to the tension of the film. However, the use of overlapping dialogue as the film moves artlessly from one scene to the next ultimately proved something of a distraction, and an unnecessarily clumsy artifice. The ambiguous nature of the final denouement also means that there is no closure.

Unfortunately we are not as deeply involved or as emotionally engaged in the plight of the characters as we should be, and we seem to be kept at a slight distance. Like a lot of other local productions, the melodramatic nature of the story and the film’s unrelentingly bleak nature and downbeat tone means that it will struggle to reach a more mainstream audience.

★★☆