Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Warwick Thronton

Stars: Bryan Brown, Sam Neill, Hamilton Morris, Natassia Gorey-Furber, Ewen Leslie, Matt Day, Thomas M Wright, Tremayne Doolan, Trevan Doolan.

Sweet Country is the sophomore feature film from indigenous filmmaker Warwick Thornton, best known for his acclaimed, award winning 2009 drama Samson and Delilah. This is only his second feature film, but in the decade since then he has been busy with short films, television projects and documentaries like We Don’t Need A Map, which premiered at the Sydney International Film Festival in 2017.

Set in the Northern Territory in the 1920s, this bleak, brutal and powerful outback western explores themes of racism, injustice, frontier justice, hardship and violence, which give it a timeliness and a topical relevance. Sweet Country hit local cinemas on the eve of the controversial and divisive Australia Day holiday and it is a painfully relevant look at the clash of cultures and race relations in this country.

The title itself is pretty ironic – on the one hand it reflects the harsh natural beauty of our land, but on the other it looks at the recent history and mistreatment of the aboriginal people from a uniquely personal indigenous perspective. It also explores how the social structure of the white settlers – their churches, saloons, towns, and even their laws – have been imposed on the indigenous population. Inspired by a true story of an aboriginal who killed a white farmer in the 1920s, Sweet Country has been written by Steven McGregor (Redfern Now, etc) and David Tranter. This is the first feature script for Tranter, who hails from a background in the sound engineering department, and who has drawn upon traditional aboriginal stories passed down through his grandfather’s family.

Sam Kelly (a strong debut performance from aboriginal actor Hamilton Morris) is an indigenous worker who lives on the cattle station owned by Fred Smith (Sam Neill), a deeply religious and Christian pioneer. He treats Sam and his wife Lizzie (newcomer Natassia Gorey-Furber) kindly and with compassion. But he agrees to loan Sam out to his new neighbour Harry March (Ewen Leslie), who is trying to establish himself on the unforgiving land.

A boorish alcoholic who is psychologically damaged by his experiences of fighting in the trenches during WWI, March is abusive towards Sam. He also badly mistreats the mixed heritage teenage boy Philomac (played by twin brothers Tremayn and Trevan Doolan) who is also on loan from another neighbourly rancher. He chains Philomac up to a rock. March sends Sam out to round up his cattle, and while he is out he brutally rapes Lizzie. He then sends the pair packing.

Philomac manages to escape and flees to safety, eventually hiding out behind the latrine on Smith’s property. March tracks him to Smith’s ranch and accuses Sam of hiding the boy inside the house. He fires a couple of shots. A gunfight erupts, and Sam is forced to shoot March in self-defence. He and Lizzie then flee into the harsh outback to hide knowing that he will not get a fair hearing about what happened.

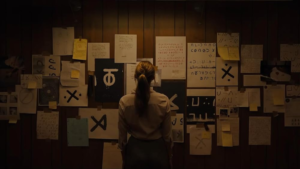

A posse is sent out to search for Sam, led by the reluctant Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown). However, they are turned back. It is only when Lizzie becomes too heavily pregnant to keep hiding that Sam turns himself in. He is put on trial, a hearing that explores questions of fairness, justice, indigenous rights, land rights. The hearing is conducted in a makeshift courtroom set up outside the local pub.

This is a visceral and violent film, and Thornton’s direction is unflinching and muscular. The film is suffused with a palpable sense of anger and indignation. He maintains a measured pace throughout. Thornton and his editor Nick Meyer also use sharp flashback sequences and small vignettes to give us some insights into a couple of the characters.

Thornton draws solid performances from his cast. Brown is typically dry and laconic here and he brings an ambiguous quality to his Fletcher. Matt Day is Taylor, the fair-minded judge trying to impose a sense of reason and justice in this inhospitable environment, much to the disgust of the townsfolk. Leslie has often played unhinged or obsessed characters, but his March here is a nasty piece of work with few redeeming features. Neill is good and brings a quiet strength to his role as Smith, who is eager to see that Sam is not the victim of a brutal and easy rush to execution. Thornton has also cast a number of locals and non-actors in small roles here, and it is their obvious connection to both the land and the material that resonates strongly. Morris, in particular, brings a sense of quiet dignity to his portrayal of the wronged Kelly, a man who knows he won’t find a fair hearing in the white man’s court. His features are hugely expressive and speak of the pain of injustice and dispossession.

Sweet Country is also a visually stunning film. Thornton has shot the film himself and his widescreen lensing makes the most of the harsh, sundrenched setting and expansive skies. He captures some superb images that bring to stark life the desolate and hauntingly beautiful landscapes. The landscapes are truly the star of the film. Thornton has eschewed a traditional soundtrack to underscore the drama, and he uses the natural sounds of the outback as a backdrop. He effectively uses Johnny Cash’s gospel anthem Peace In The Valley at the end to give the material an ironically optimistic note.

★★★☆