by GREG KING

“I love films that I’m mesmerised by, that I can’t take my eyes off,” says Julia Leigh, Australian novelist turned filmmaker. “Personally I don’t like seeing a film on Thursday night and then forgetting it by Friday morning. My hope is that Sleeping Beauty is a memorable film.”

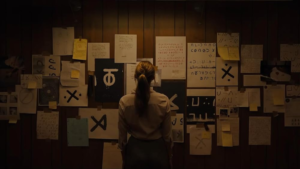

Her debut film, the erotic psychological drama Sleeping Beauty, is certainly a memorable film. It is a provocative but ultimately pointless study of sexual dynamics, female sexuality, identity, liberation, and willing female submissiveness. The central character is Lucy (played by Emily Browning, from Sucker Punch, etc), a cash-strapped university student who is juggling three part-time jobs to make ends meet. In desperation, she takes on a high paying job in a high-end brothel. At first she starts out as a waitress, but is soon promoted to “sleeping beauty”, which is when things become a little creepy. She is drugged, stripped, and, while unconscious, becomes a baby doll who is groped and caressed by older lonely men who do all manner of perverted things – except penetration, which is strictly forbidden – that border on the necrophilic.

“It’s very hard for me to say where a creative project comes from,” Leigh says when asked about the genesis of the film. “It’s almost as if you answer a question with hindsight. I guess I was always aware of the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty. Like many people I had heard it as a child. But many fairy tales have deep roots for many of us. And the original fairy tale, not the Disney version, was quite brutal. I was also aware of King David, in the Bible, heading out to spend the night alongside sleeping virgins. “I was also aware of contemporary practices of sleeping girls on the Internet. I had read two well known novellas – one by Yasunari Kawabata, one by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which both tell the story from the point of view of an older man who pays to spend the night alongside a drugged sleeping young girl. The idea of a sleeping beauty was out there, it is something that exists. I guess I’m responding to that and transforming it into a film.”

Leigh is a qualified lawyer who has never practised, she holds a Ph.D in English from the University of Adelaide, and she has studied and taught abroad. But she is best known as a novelist, and her two previous books The Hunter and Disquiet have received critical acclaim at home and abroad. (The Hunter has also recently been adapted into a film in 2011 with a solid cast including Sam Neill, Willem Dafoe and Frances O’Connor.)

Her decision to direct a feature film was borne out of her love of watching films. “I guess my choice of going into film making came from my love of watching films. I didn’t really wake up one day and say ‘I’m going to direct a feature film tomorrow,’” she explains.

The scripting process was actually a stepping stone from writing a novel to making a film. She also did a lot of pre-production preparation, working closely with cinematographer Geoffrey Simpson to develop the mise-en-scene. Early in the filming process, Leigh had decided that she wanted to use long single take shots to cover certain scenes, which gives an almost voyeuristic quality to the film.

“I actually found it a useful thing to do was to watch films with the sound turned down, and ask myself ‘Where’s the camera? Where’s the camera?’ But I did an awful lot to prepare, and I was lucky enough to work with wonderful collaborators and heads of department.

“I wanted to make a beautiful film. This film could have been told as a gritty, hand-held grimy film but I chose to make a beautiful film. Because if you take pleasure in beauty it can have its rewards.”Leigh speaks at length about the casting process. Integral to the film’s success is the brave performance from Browning (replacing Mia Wasikowska, who dropped out due to a scheduling conflict). Browning is nude or semi-naked for much of the time, yet manages to convey Lucy’s emotionally fragile state. “She was very brave,” acknowledges Leigh, “but I would have to say that she knew that what she was doing was in keeping with the script, and she embodied the character. “She has a strange beauty, not a cookie-cutter kind of beauty. She read the script and she understood the script, and it resonated with her. In the way of all great actors she made the role her own. When you create a character it’s an abstract. But as soon as a real person is there they embody it, and it’s very different, “Emily put down a demo on tape and I found I couldn’t take my eyes off her,” elaborates Leigh. “I find her very beautiful.”

Rachael Blake (from Lantana, etc) is suitably cold and aloof as Clara, the madame of this high-class brothel that caters to a rather unusual clientele. “I really liked Rachel Blake because I find her not too stern,” continues Leigh. “She has a mix of genuine care for Lucy, her charge, and also a callousness. I think she’s a keeper of secrets, and Rachel brought terrific poise to the role.”

The portraits of the men were incredibly important to the film. “I mean, some tell the story of Lucy, and the story of youth, but it’s made whole by the portraits of the older men,” Leigh says. The men who sleep with the narcoleptic Lucy are played by the urbane Peter Carroll, a sadistic and very creepy Chris Haywood, and a brutal Hugh Keayes-Byrne, who will forever be remembered as Toecutter from the original Mad Max. “I’ve never seen Mad Max. I must be the only person who has never seen Mad Max,” she confesses with a laugh. Leigh cast theatre veteran Carroll because he has a beautiful, wise, experienced face that suited the character. He also has an important monologue, which gives some insight into the role that the sleeping beauty plays in the lives of these men.

Leigh also speaks candidly about the role played by Oscar-winning writer/director (and Palme d’Or winner) Jane Campion (The Piano, etc) in becoming a mentor for her during the filming process. “I was introduced to Jane by Screen Australia, who wisely thought that I should have someone on hand who I could ask questions of. Jane read the script and I held my breath hoping that she would respond to it, and she did, and she agreed to come on board as a mentor. She was on board for most of the pre-production, and we always knew she would be overseas during the shoot. And she returned in post production, and I just have to say that when she saw an early cut of the film she encouraged us that we were on the right track, and I got a great deal of comfort from that.”

Sleeping Beauty screened at Cannes at the 2600 seat Lumiere Theatre where it drew some negative reviews and comments. The film caused something of a controversy, which is great publicity for a first-time filmmaker unsure of how an audience would react. But Leigh prefers to ignore the fuss, and concentrate on the positives from the screening. “We had just an incredible, wonderful experience,” she says. “At the end of the film it’s the tradition for the film makers to stand up and acknowledge the audience. We in turn had a standing ovation. I must admit that was a very strange but unforgettable experience. I can’t complain.”As for what is next for Leigh? “I hope to continue to make films and write books,” she says. “I’m trying not to typecast myself., I’m trying to resist hyper-professionalising my reputation, so I would love to continue to do both.”