Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Richie Mehta

Stars: Rajesh Tailang, Tannishtha Chatterjee, Irfan Khan, Anurag Arora, Shobha Sharma Jassi.

A grim, emotionally wrought tale about a father’s desperate and harrowing search for his missing son Siddharth is certainly a welcome change from the usual Bollywood style of filmmaking with its colourful dance sequences and musical numbers and inordinate running time. This moving drama offers some insights into life in contemporary India and gives audiences a taste of an exotic culture beyond our understanding or experience.

Mahendra (played by Rajesh Tailang) is a chain wallah eking out a living on the teeming, crowded streets of New Delhi by fixing people’s watch chains and zippers. As the family was desperate for some extra cash, he had sent his twelve year old son Siddhu (Irfan Khan) to a different town to work. Siddhu was due to return home for the Diwali celebration, a festival of light, but when he fails to show up the family become concerned. He learns that Siddhu ran away from his work place two weeks earlier and hasn’t been seen or heard from since.

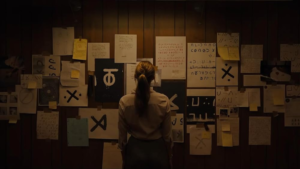

Mahendra doesn’t have a photograph of his son to show police, and he doesn’t even know how to spell his son’s name, is unsure of his age, and is unable to provide a detailed description. He doesn’t know how to go about finding Siddhu, and has no way of tracking him down. The only clue he has is a place called Dongri, which is apparently where a lot of kids end up. But Mahendra is technologically illiterate and has little hope of finding this mysterious place. And many people he asks for help do not recognise the name.

Initially Mahendra and his wife Suman (Tannishtha Chatterjee, from Brick Lane, etc) find little sympathy from their friends and family in their search. Even the police do not seem very interested, as child labour is supposedly illegal. And the fact that Mahendra doesn’t have a photograph of his son doesn’t help. As travelling from one city to another as part of the search is expensive, Mahendra is forced to find extra work on the streets to save up for a bus fare, including working for Mukesh-Bhai (Mukesh Chhabra), the seemingly cruel gay boss of a street gang.

Tailang, who will shortly be seen in the sequel to The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, brings a sense of compassion and increasing sense of desperation and confusion to his nuanced performance as the illiterate Mahendra who goes to extraordinary lengths to find his son. Chatterjee is sympathetic and touching in a smaller but important role as Suman, who is frustrated by her husband’s inability to provide a decent living for the family.

The film begins somewhat slowly, but the pace and suspense picks up as Mahendra’s search becomes more desperate and more heartbreakingly futile. Apparently the story that unfolds here is not unique, as thousands and thousands of children go missing in India every year. Some are taken into trafficking, some into slavery, some into sexual slavery, some are taken for organs, and some are taken for indentured servitude in different countries.

Siddharth is the sophomore feature film for Toronto-based filmmaker Richie Mehta, who himself is of Indian descent and has a good understanding of the culture and economic problems facing contemporary India. His debut feature was Amal, about a rickshaw driver who inherited a fortune from one of his customers and found his life dramatically altered. Here again Mehta explores the class structure of India and shows us the disparity between the rich and the poor.

But he also suffuses the film with a sense of hope and optimism as he shows us the incredible generosity of spirit of Indians as many go out of their way to help Mahendra in his increasingly desperate and futile quest. Mehta was apparently inspired by the story of a rickshaw driver he encountered who was trying to find his missing son, which gives a personal quality to this story.

Siddharth offers us a warts and all look at modern India, as Mehta effectively immerses us in the sights, the smells and the sounds of the teeming, crowded streets and urban squalor of New Delhi. Working closely with cinematographer Bob Gundu, who also worked with Mehta on his short film projects and experimental projects, he brings a documentary like realism to the film through the use of hand held cameras. The film has the look and feel of some of those classic postwar neorealist films from Europe, like The Bicycle Thief, et al.

Siddharth offers a bleak and uncompromising view of contemporary India, but it is a heart wrenching and eye-opening journey that may not hold broad appeal.

★★★