Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Bruno Barreto

Stars: Miranda Otto, Gloria Pires, Nancy Middendorf, Treat Williams, Marcello Airoldi, Lola Kirke.

Elizabeth Bishop is a Pulitzer Prize winning author regarded as one of the four greatest female poets of all time, but she is a writer who I had never heard of before.

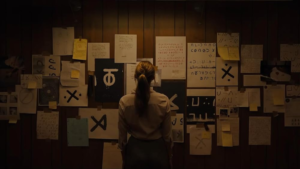

Reaching For The Moon charts the relationship between Bishop and landscape architect Lota de Marcedo Soares. The film is set Brazil in the 50s and 60s. Suffering from writer’s block Bishop (played by Australian actress Miranda Otto, best known for the epic Lord Of The Rings trilogy) follows the advice of fellow poet and mentor Robert Lowell (Treat Williams) and heads off to South America to recharge her batteries. There she reconnects with Mary (Nancy Middendorf, from Boardwalk Empire, etc), a former college friend. Tracy is the companion of renowned landscape architect Lota Soares (Gloria Pires), and Elizabeth is invited to spend some time with the couple.

Initially Elizabeth feels uncomfortable in her strange new surroundings, but slowly finds herself drawn towards the strong willed Lota, and a relationship develops. Lota builds Elizabeth a studio where she can write, and she attempted to pacify Mary by helping her to adopt a child. But the love triangle between the three women was complicated, messy and fiery. Reaching For The Moon explores the complex relationship between Bishop and Soares, which is complicated by Bishop’s battle with alcohol, and Soares’ battles with depression, jealousy and her obsession with creating the landmark Flamengo Park in Rio de Janeiro. But this tempestuous relationship apparently inspired some of Bishop’s best work, and she grew in strength as time progressed. When she returned to New York for a teaching position, it marked the end of their relationship, and Lota grew depressed.

Reaching For The Moon is not a conventional biopic about a tortured artist and the creative process, rather it is an unconventional love story set against the backdrop of the 50s and 60s when gay romances were kept secret. The film doesn’t delve too deeply into gay politics. The genesis of the film actually began in the 50s when producer Lucy Barreto actually met Bishop and Soares in a restaurant and was fascinated by their intimate connection. In 1995 author Carmen L Oliveira wrote a novel Rare And Commonplace Flowers, which depicted the tempestuous relationship, and Barreto purchased the film rights. From the outset she always envisaged Pires, best known for her appearances in a lot of telenovellas, to play Soares.

Scriptwriters Matthew Chapman (Runaway Jury, Color Of Night, etc) and television writer Julie Sayres (Knots Landing, etc) have adapted their screenplay from Carolina Kotcho’s earlier adaptation of the novel, but their treatment is quite detached, and it is hard to become emotionally invested in these two characters. The drama is book-ended by Bishop’s poem One Art, but apart from that we get a few samples of her poetry, and we never really get a sense of why she is so highly regarded.

Otto is waspish aloof, distant and cold as Bishop, who made little effort to be likeable, but she also finds her fragility and her internal emotional turmoil and insecurities, and her wonderfully nuanced performance gives the film a strong central focus. In her first English speaking role Argentinian actress Pires is volatile, and passionate as the headstrong Lota. The two women offer a contrast in style and temperament that should have added some spark to the material.

The director is Bruno Barreto, best known for his film Dona Flores And Her Two Husbands, whose treatment of the material is sensitive. He has made compelling thrillers like Last Stop 174 and Four Days In September, but here his direction is very prosaic and the film barely gets out of first gear. It is nearly two hours long, and by the end we begin to feel every minute of those two hours. This was a turbulent time in Brazil’s history with the 1964 coup and some political powerplays, but we never get a hint of these internal tensions and sense of danger.

However, the film has been beautifully shot, and cinematographer Mauro Pinheiro jr makes the most of the lush, gorgeous locations. Jose Joaquim Salles’ production design captures the period detail well, and his recreation of Soare’s grand house is spectacular.

★★☆