Reviewed by GREG KING

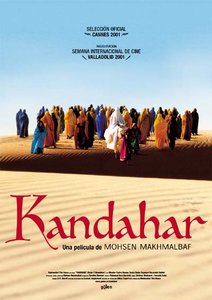

Director: Mohsen Makhmalbaf

Stars: Nelofer Pazira

Given the US sanctioned war against terrorism that is currently devastating much of Afghanistan, this new film from acclaimed Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf (Gabbeh, etc) is both timely and has an immediacy and urgency. Kandahar gives audiences an insight into a land that few know about, and, in uncompromising fashion, explores the hardships endured by the people living in this impoverished land under the repressive regime of the fanatical Taliban and their brand of religious extremism.

Here women are treated as third class citizens with few rights. Women are forced to hide beneath the bulky burka (a head to toe headdress that conceals them from the outside world), and are prohibited from leaving the house unaccompanied by a male relative. Girls were also forbidden to attend school, and now less than 5% of adult females can read or write. Doctors are forbidden to talk directly to their female patients and can only examine them through a hole in a cloth strung across their ill-equipped surgery. Boys are taught the power and righteousness of both the Koran and the Kalishnikov in school. And, over the past 20 years, an average of one person has died every five minutes from the ravages of famine, drought, disease or war.

The statistics are daunting and horrifying, but the film’s succinct plea that this impoverished region desperately needs humanitarian aid from the west is poignant and heartfelt, and, one feels, likely to be ignored.

The film is largely seen from the viewpoint of Nafas (Nelofer Pazira), an Afghan born journalist who fled to Canada a decade ago. Her sister was injured by a landmine during the escape and had to remain behind. But now Nafas has received a letter from her sister, stating that she has suffered enough and plans to commit suicide during the final eclipse of the millenium. Because of a delay through smuggling the letter out of the country, Nafas has only three days to try and find her sister. Denied a visa, she is forced to enter the country illegally from Iran, relying on help from smugglers and a variety of travelers to reach Kandahar. Nafas’ journey is fraught with peril, but Makhmalbaf’s film finds some strange and memorable scenes of beauty amidst the inhospitable and bleak terrain.

Ebrahim Ghafouri’s cinematography is breath takingly beautiful, and captures some unforgettable images. The women’s costumes are brilliantly coloured, almost in direct contrast to the bleakness of their existence. And a group of amputees hobble across the desert to try and reach prosthetic limbs being dropped from a UN medical transport. But Kandahar is also a film that highlights the cruelty and blatant injustices perpetuated in Afghanistan in the name of religion, but this emotionally charged film exerts a powerful effect on the audience as well.

Although Kandahar is loosely based on a true story, Makhmalbaf and his cast have largely improvised much of the dialogue and drama on location, giving the film an almost unrehearsed, documentary like realism that will resonate with audiences long after it has finished.

★★★