Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Takashi Miike

Stars: Ebizo Ichikawa, Koji Yakusho, Eita.

Japan in the 17th century. The former feudal structure is crumbling, and as shoguns and war lords lose their power, many former samurai find themselves out of work and impoverished. Many find it hard to eke out a living or support their families, and would turn up to the house of a powerful chief asking permission to commit ritual suicide. It is believed that committing suicide in such lavish surroundings will enhance the samurai’s death. “The greater the house where he dies, the more honor he regains.” But many samurai would use this as a means of soliciting money or finding work.

Hanshiro (kabuki actor Ebizo Ichikawa) is one such ronin (or disgraced samurai), who arrives at the house of Li, and begs permission to commit suicide in the courtyard. But the chief official Kageyu (Koji Yakusho) is suspicious, and in an attempt to dissuade Hanshiro he tells him the story of Motome (popular tv star Eita), a young samurai who recently approached him with a similar request. But when the young warrior asked for money instead, Kageyu called his bluff and forced him to follow through on his threat of suicide, even though the young man had sold his sword and only had a wooden blade. But there is another layer to this story as Hanshiro tells Kayegu of the personal tragedy that has brought him here.

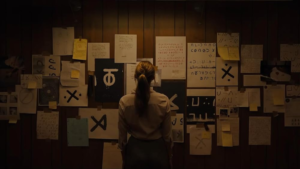

The drama unfolds in a series of elaborate flashbacks. Hara Kiri: Death Of A Sumarai is a remake of Masaki Kobayashi’s 1962 film, which was banned in this country due to our rather strict censorship laws of the time. The film has been directed by prolific Japanese filmmaker Takashi Miike (13 Assassins, Audition, etc), who is known for his violent gangster movies, his samurai movies and his occasional foray into horror. Here he returns to Japan at the end of the feudal system, the setting for many of his films, and Hara Kiri looks at the hypocrisy of an implacable, cold hearted ruling class that placed its own self-interest above humanity and common decency.

Miike is well known for the intensity of the action in many of his films, but here he handles the material with uncharacteristic restraint. The film unfolds in deliberate, measured style with an emphasis on character over action, although the climax shows off Miike’s talent for choreographing spectacular and complex fight sequences. Although Hara Kiri remains reasonably faithful to Kobayashi’s original, Miike stamps it with his own unique visual style and brings a lyrical beauty to the film. He also brings a stiff formality to this dying world of samurais and feudal war lords.

Miike and his cinematographer Nobuyasu Kita have shot the film in 3D, but the process is used subtly to add depth and spatial awareness to the locations rather than overwhelm the audience. Ryuichi Sakamoto’s haunting and evocative score also enhances the drama. This beautiful looking film is an examination of the dying samurai code in feudal Japan, and it looks at their code of honour, loyalty, respect, and revenge.

★★★