Reviewed by GREG KING

Director: Margarethe Von Trotta

Stars: Barbara Sukowa, Janet McTeer.

The banality of the biopic?

Hannah Arendt is regarded as one of the most important, provocative and controversial thinkers of the twentieth century. It’s probably not surprising that Arendt is an anagram of ardent, because she certainly was an outspoken and passionate thinker and writer. A philosopher, intellectual and political theorist, she coined the phrase “the banality of evil” after covering the war crimes trial of former Nazi Adolf Eichmann. This biopic of the controversial figure however only spans about four years of her life, but they were to define her reputation and legacy.

Of Jewish ancestry herself, Arendt was a lecturer at the New School in New York who regularly engaged in articulate discussions with friends and colleagues in her apartment. In 1961 she was assigned the task of covering the Eichmann trial in Israel for the prestigious New Yorker magazine. In her report though she dismissed Eichmann as boring and harmless, an ordinary bureaucrat unable to think for himself and who was merely following orders in the well-oiled machinery that was Nazi Germany. She also suggested that many European Jewish leaders were complicit in their own fate as they willingly passed on lists to the Nazis in the hope of more favourable treatment.

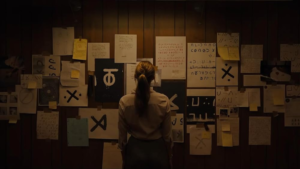

Following the publication of the article, Arendt faced an extreme and vicious backlash as former supporters turned their back on her. She received lots of hate mail, death threats, and even her tenure at the school was threatened by her nervous superiors. Arendt spent much of her time defending her controversial stance and trying to restore her reputation. She spoke of the importance of thinking and asking questions rather than merely accepting what is happening around you.

The director here is Margarethe Von Trotta, a leading German filmmaker at the forefront of the emergence of the new wave of German cinema, who is often spoke of with the same reverence afforded the likes of Fassbender and Herzog. And it is easy to see her attraction to Arendt’s story because many of her films have dealt with formidable and strong female characters. But despite all the potential for a great piece of drama, this biopic is something of a misfire.

The film is anchored by Barbara Sukowa’s superb performance as Arendt. Although Sukowa (who has worked with Von Trotta several times before) doesn’t physically resemble Arendt, she captures her inner turmoil, her strength of personality, her arrogance, her feisty personality and her uncompromising nature. It is a strong and commanding performance which has won her numerous accolades and even the Best Actress Award at the Bavarian Film Festival. But it is a performance that deserved better than this underwhelming material.

Janet McTeer (from Albert Nobbs, the tv series Damages, etc) is also very good as the writer Mary McCarthy, one of Arendt’s close friends and staunchest supporters.

Written by Pam Katz and director Von Trotta, who both collaborated on Rosenstrasse, Hanna Arendt is slow paced and very intellectual in nature. The script was also partially inspired by Elizabeth Young-Bruehl’s 1982 biography and many letters written by Arendt herself. Von Trotta aims for a documentary-like realism. The period detail is good, as is Volker Schaefer’s production design. Cinematographer Caroline Champetier has shot the film in mostly warm, brownish hues, but visually it is suited more to a telemovie than the big screen.

The film is heavily dialogue driven, and it lacks broad appeal. Nor do we get many insights into Arendt’s complex character. But unfortunately this coproduction between France, Germany and Luxembourg is heavily theatrical in its staging, as most of the action is confined to the rarified world of New York’s intelligentsia and their community. It doesn’t make for the most compelling screen drama.

Actual black and white archival footage of Eichmann’s trial has been incorporated into the film which adds a sense of authenticity, but the 1975 film The Man In The Glass Booth was a far more powerful exploration of the trial and complex issues of guilt and responsibility.

★★☆