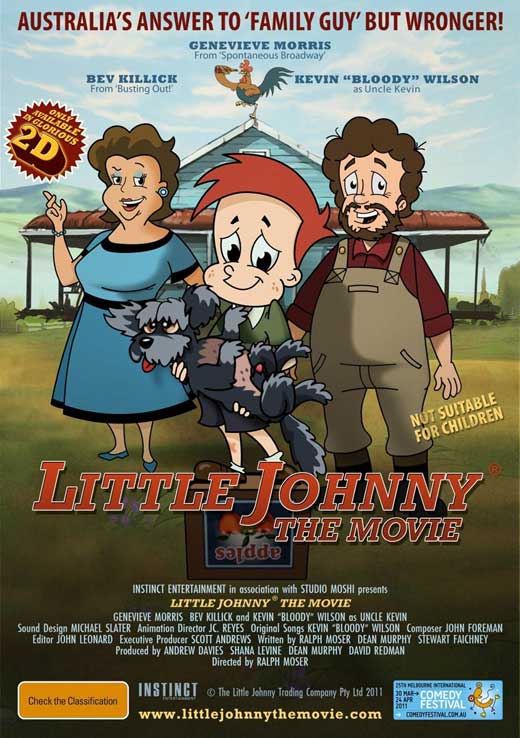

by GREG KING.

We’ve all heard some of those “little Johnny” jokes, now we can discover their origin. Little Johnny is a new animated mockumentary that discovers the “real boy” behind the jokes, and also looks at his dysfunctional family that provided the inspiration for much of the humour. The film itself is the brainchild of Ralph Moser and his co-director Dean Murphy and screenwriter Stewart Fainchey. The three have a long established partnership and have worked together on a number of films, including two with Paul Hogan – Strange Bedfellows and the recent Charlie And Boots.

“Little Johnny is very inspired by Monty Python, The Goodies, from when I was a kid, and of course the Looney Tunes cartoons. It’s not Benny Hill, but it does have a kind of irreverence.” Sipping a coffee in a cafe just a short walk from his South Melbourne office, where he is heavily involved in post production work, Moser discusses the genesis of the film Little Johnny.

A life-long film buff since he first snuck out of his bedroom to watch The Time Machine on television late one night as a six year old, Moser has been fortunate enough to work in the film industry for much of his life. “I was traumatised, but at the same time I was absolutely enthralled at what the power of cinema was,” he recalls of the experience, “and I knew then that this was the way I was going to go.”

Moser worked in a video library when he was a student, a bit like Quentin Tarantino, and noted the reactions that certain movies would have on different people. “It’s amazing what translates for an audience and I guess I was always fascinated by that.”

Moser comes to direction through a background in production design and story boarding. Some great directors, like Sam Raimi, have also started their careers through storyboarding. “Production design is about the look,” he explains, “but to me it’s about the staging. I learned very early on that a really good set can telegraph the story. In essence when you have a series of images put together to tell a story that’s what cinema is all about. Turn down the volume on a great movie and watch it and it will still tell itself through a series of images.”

Animation is very much based on story boards, it’s also the very purest form of storytelling as far as the storyboard artist goes. Moser’s training was through storyboarding, and he worked his way up to production design. His credits include local productions like Let’s Get Skase, Sensitive New Age Killer, Hating Alison Ashley, and Till Human Voices Wake Us. Moser also experienced working on large scale Hollywood productions, including Where The Wild Things Are, which was filmed in Melbourne, and Russell Mulcahy’s television remake of On The Beach.

“Working on Where The Wild Things Are was a whole different level,” he elaborates. “It was being exposed to the Hollywood machine, where you do a vast amount of work that gets seen by relatively few people. I was very lucky to work with Ken Barrett, who was the production designer on Lost In Translation. He’s just a tremendous designer, and he had a very unusual way of approaching his material. If something was a cliché, he’d steer in the opposite direction. I don’t always work that way. Sometimes I think there are times when you want to celebrate those clichés, and in Little Johnny we do.”

Moser makes his directorial debut with the animated feature Little Johnny. He admits that his decision to direct was a natural progression. “I’ve spent so much of my time fascinated by what directors do and how they interact with the cast, and I’ve adopted a lot of that along the way. A lot of my work was done by the time directors turn up on the set. I’m often in the wings watching it all, after having been there eight hours before the crew arrives. So in my own hazy way I’ve picked up a lot.”

The genesis of the project came when his long time associate Dean Murphy on a number of scripts when he was told a “little Johnny” joke. “I’m not good at telling jokes, but I’m a great joke listener,” Moser confesses. “I was on the floor laughing. It was a very funny joke, but I can’t repeat it. He then said: ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting to make a movie about little Johnny.’ I had no idea how to construct something based on a joke. We did a little bit of research. We looked on the internet and saw about two million references to him, and we thought there is obviously a market.

“The jokes are actually out there in the public domain, and they have been told and retold in different ways. We found the versions that worked best with us and we reworked them a little bit. Then we started cutting them up and restitching them together and seeing how they played as a narrative. There was already a kind of structure to the story from those jokes if you gave it a bit of careful editing. From that we started to incorporate the jokes into the screenplay. Then I realised that, as funny as those jokes are, the minute you line them up one after the other, you tend to just have a series of gags that play out, without the story to bolster it. I think that all these things hinge on the narrative, and I needed to find a human story to tell. Even if it’s a comedy you still need to find some sort of reality to base it on and anchor it.”

From that spark, Moser and his film making associates went away for three days of writing, and the jokes and the wine flowed freely. They structured the story, got the narrative to the point where it all made sense, just plotting wise. “In three days we just structured the story. There was a lot of laughs. I can’t recall ever having a sorer stomach after writing.

“The only way I would be interested is if we could do something different. Maybe if we animated it. And even better still if we did something like a mockumentary. Being a big fan of Spinal Tap it was always going to be on the cards. And it started from there.”

Moser also thought that a small country town was the perfect setting for little Johnny’s world. There was something about it where time had stood still. And something about little Johnny jokes also feels like it’s from a certain period, kind of like before the burning of the bra, before political correctness consumed the world. There’s something very innocent about this world. “It’s like freshly mown grass, something that never goes away,” he explains. “It’s a feeling. That’s what I want to capture. If we’re going to do it then let’s set it back then when little Johnny was a kid. I don’t want to know what he looked like when he got older; I want to know him as a little boy in a little town. And from that he was born.

“Part of that nostalgic feeling does come from those cartoons that we grew up with as kids – you can’t go past Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng or even a Bugs Bunny cartoon. It was limited animation, but there’s something about them – you can’t beat those looks. Part of their genius was born out of necessity, and I knew that if we were going to make this movie we’d have to have that same mother of invention. I knew that in our case we had a very limited budget. We were out there trying to push a very adult animated feature film in Australia which has never been done before. I take my hat off to Adam Elliot’s Mary And Max. I loved the movie, that claymation stuff, and I thought that’s our guiding light. We’ve got to do something similar to that in 2D. Everything’s 3D CGI animation and also in 3D, but our movie harks back to a simpler time, we’re actually celebrating the whole 2D nature of it. It’s very retro style.

“I would love to have done it in hand painted style, which would mean going back to the old cell animation and shooting it all, frame by frame, and using multi-plane camera work like they did on the old Disney cartoons, but that exercise is extremely costly. Even though shows like The Simpsons, which has been around for 20 years, and Family Guy, are still hand drawn and done over in Korea and India, they have a very well established style. And to do that from scratch the R&D alone just to get the characters built would be very expensive. We realised that we were going to have to rely on computer assisted technology, and we were going to have to rely on a program called Flash. It’s no different to cell animation like the old days, but you can build libraries of expressions and it helps you keep your drawings alive without having to go to single frame animation the whole way. So we had to fight every step of the way to get it looking like one of those old Warner Bros cartoons. And it meant relying on an animation director who had a whole lot of experience and got what we were coming from. So I teamed up with a local animator, who’d done a lot of work with Disney and Hanna Barbera when they were based in Sydney. After those two studios closed down it was hard to find that kind of work, so they do a lot of children’s tv shows for the Cartoon Network, etc. I put together a team of animators that would be capable of doing what we wanted.”

Moser produced some 2500 hand drawn frames in black and white drawings, and even though they were very crude it was enough to nail the final structure of the story.

Uncle Kev, the wayward uncle and Johnny’s mentor, was probably the trickiest role to cast. Kevin Wilson was a latecomer to the piece, and proved to be a blessing for the film makers. “He’d never done a movie before, but we thought the guy had to be capable,” Moser explains. “And we ended up arranging a chat over the phone, and we spoke to him. He’s exactly what you think Kevin Bloody Wilson would be like – he is the most down to earth honest to God person you could meet. He is that larrikin spirit that just embodies rural Australia to me. And there is something about the nature of language in comedy where you can drop the F bomb as much as you like and if you say it a certain way you can get away with it.. He could swear all day long, and you know there’s no malevolent intent behind it and it’s from the heart. You embrace him for it, you love him for it.

“I’ve just noticed that in his book, when he got the Order of Australia he got the award at the same place he was arrested for using foul language twenty years earlier. The irony of that, and here he is making a movie where he plays himself basically as an animated character where he uses that kind of language and we celebrate him for that. And it’s almost as if I wanted to celebrate that Australian larrikinism, and he is that.”

Wilson has also provided a number of original songs for the film, and according to Moser, they have that authentic sound of those old Sun records from the ‘50s. A lesser known fact is that Wilson has also written a number of songs for Slim Dusty.

Genevieve Morris, who is better known to television audiences as Barbara in the series of ANZ bank advertisements, was immediately cast as little Johnny. In much the same as Nancy Cartwright provides the voice for Bart Simpson in the long running animated series, Genevieve had that right amount of raspiness to her voice, and it was almost as if she became the character of little Johnny. “It would be great to have a little kid, but some of the things he says would probably get me arrested” laughs Moser. “She’s a fiercely intelligent woman and she brings that to the role. I thought I’m not listening to a woman, I’m not listening to a man trying to be a kid, I’m listening to a little boy who’s so excited that he’s about to wet his pants. And it was brilliant. She can switch on and switch off, it’s remarkable.”

“We were dealing with children, but by the same token I wanted it to reflect the adult world as told through the eyes of a child, so it’s about our inconsistencies as grown-ups rather than children. That’s the hardest kind of thing to do, because you can’t get children to play those parts. Using Genevieve in that role kind of papered over that.

“That’s the magic of animation. I’ve tried to keep it as fresh as I could, because you can over engineer it. I think a lot of the big Hollywood films suffer from it. When it’s done badly it seems over rehearsed, it doesn’t seem fresh, the lines seem like they’ve been said 100 times. We only had six days to record the dialogue for the whole film – and with one call back. So it was all very fresh. If we got it we moved on. The whole film has been made that way. It’s almost like underground cinema but a whole new level because it’s the kind of cinema you can’t do underground.”

The film is premiering at the Melbourne International Comedy festival in April. In explaining this decision, Moser says: “The market is a comedy festival market, it’s not really a festival player. We figured that the comedy market would be just the right place. It’s about comedy, it’s about the nature of comedy.”

The film is also having a simultaneous VOD release, which means people from anywhere in the world can pay a small fee, log on to their computer and watch the film on tv in their own lounge room. “The idea is premature in many ways because the technology in Australia hasn’t caught up yet,” Moser elaborates. “Which is why we’re pushing for a theatrical screening. We’re trying to turn the model on its head. Our producer has been very adamant about challenging the convention of the way cinema runs, the whole distributor/filmmaker relationship. At present the model is very hard to find any room for the independent film maker. Unfortunately it’s great when you’re doing Iron Man 2 and you’ve got a marketing budget of $150million, because you can just take any bus shelter and wall paper it and say here’s our movie. But when you have no money you’re relying on word of mouth. It’s a risk, and if you didn’t take a risk you wouldn’t be in the business. That’s the nature of film making”

Moser hopes that the film will also enable audiences to have a great time. “I want them to hark back to how cinema used to be. You’d go out and watch a movie with your mates, and you’d all sit down and have a beer afterwards and laugh about it, and talk about it and have an experience. I think that so much of cinema has become sitting in a room in a darkened space and not sharing it with anyone, and I think it should be shared. You look at a small country town, and the cinema is the centre, the focal point. This was where people gathered to discuss life, and that’s what cinema should be at its best. And I thought that if I could get that I’d be very happy.”